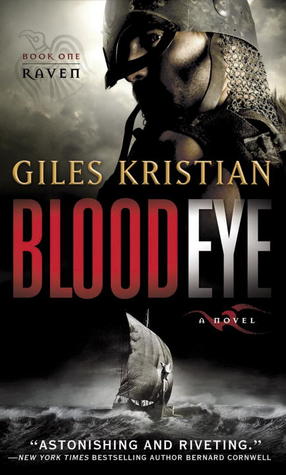

Synopsis

For two years Osric has lived a simple life, apprenticed to the mute old carpenter who took him in when others spurned him. But when Norsemen from across the sea burn his village, Osric is taken prisoner by these warriors. Their chief, Sigurd the Lucky, believes the Norns have woven this strange boy’s fate together with his own, and Osric begins to sense glorious purpose among this fellowship of warriors.

Immersed in the Norsemen’s world and driven by their lust for adventure, Osric proves a natural warrior and forges a blood bond with Sigurd, who renames him Raven. But the Norsemen’s world is a savage one, where loyalty is often repaid in blood and where a young man must become a killer in order to survive. When the Fellowship faces annihilation from ealdorman Ealdred of Wessex, Raven chooses a bloody and dangerous path, accepting the mission of raiding deep into hostile lands to steal a holy book from Coenwolf, King of Mercia.

There he will find much more than the Holy Gospels of St Jerome. He will find Cynethryth, an English girl with a soul to match his own. And he will find betrayal at the hands of cruel men, some of whom he regards as friends.

Book Trailer

Excerpt

Chapter One

It was April. The lean days of fasting and the long months of winter had been forgotten with the full bellies of the Easter feast. The people were busy with the outdoor tasks that the icy winds had kept them from: straightening loose thatch, replacing rotten fences, replenishing wood stores, and stirring new life into the rich soil of the plow fields. Wild garlic smothered the earth in the shady woods like a white pelt, its scent whipped up by the breeze, and blue spring squill sat like a low mist upon the grassy slopes and headlands, stirred by the salty sea air.

Usually I was woken by Ealhstan’s mutterings and one of his bony fingers digging into my ribs, but on this day I rose before the old man, hoping to be away catching a fish for our breakfast before having to suffer his ill temper. I even imagined he might be pleased with me for being at the task before the sun reddened the eastern horizon, though it was more likely he would begrudge my being awake before him. Fishing rod in hand and wrapped in a threadbare cloak, I stepped out into the predawn stillness and shivered with a yawn that brought water to my eyes.

“The old goat got you working by the light of the stars now, has he?” came a low voice, and I turned to make out Griffin the warrior leading his great gray hunting dog by a rope that was knotted so that the animal choked itself as it fought him. “Keep still, boy!” Griffin growled, yanking the rope viciously. The beast was coughing, and I thought Griffin might break its neck if it did not stop pulling.

“You know Ealhstan,” I said, holding back my hair and leaning over the rain barrel. “He can’t take a piss before he’s had his breakfast.” I thrust my face into the dark, cold water and held it there, then came up and shook my head, wiping my eyes on the back of my arm.

Griffin looked down at the dog, which was beaten at last and stood with its head slumped low between its shoulders, looking up at its master pathetically. “Found the dumb bastard sniffing around Siward’s place just now. He ran off yesterday. First time I’ve laid eyes on him since.”

“Siward’s got a bitch in heat,” I said, tying back my hair.

“So the wife tells me,” Griffin said, a smile touching his mouth. “Can’t blame him, I suppose. We all want a bit of what’s good for us, hey, boy?” he added, rubbing the dog’s head roughly. I liked Griffin. He was a hard man but had no hatred in him like the others. Or perhaps it was fear he lacked.

“Some things in life are certain, Griffin,” I said, returning his smile. “Dogs will chase bitches, and Ealhstan will eat mackerel every morning till his old teeth fall out.”

“Well, you’d better dip that line, lad,” he warned, nodding southward toward the sea. “Even Arsebiter here has less bite than old Ealhstan. I wouldn’t get on the wrong side of that tongueless bastard for every mackerel the Lord Jesus and His disciples pulled out of the Red Sea.”

I looked back to the house. “Ealhstan doesn’t have a right side,” I said in a low voice. Griffin grinned, bending to rub Arsebiter’s muzzle. “I’ll bring you a codfish one of these days, Griffin. Long as your arm,” I said, shivering again, and then we parted ways, he toward his house and me toward the low sound of the sea.

A pinkish glow lay across the eastern horizon, but the sun was still concealed and it was dark as I climbed the hill that shielded Abbotsend from the worst of the weather blowing in from the gray sea. But I had walked the path many times and had no need of a flame. Besides, the old crumbling watchtower stood visible at the hilltop as a black shape against a dark purple sky. Folk said it was built by the Romans, that long-disappeared race. I did not know if that was true, but I whispered thanks to them anyway, for with the tower in sight I could not lose my way.

My mind wandered, though, as I considered taking a skiff beyond the sea-battered rocks the next morning to try to catch something other than mackerel. You could pull in a great codfish if you could get your hook to the seabed. Suddenly, a metallic tock stopped me dead and something whipped my eyes, for an instant blinding me. I dropped to one knee, feeling the hairs spring up on the back of my neck. A guttural croak broke the stillness, and I saw a black shape swoop up, then plunge, settling on the tower’s crumbling crown. It croaked again, and even in the weak dawn light its wings glinted with a purple sheen as its stout beak stabbed at its feathers. I had seen similar birds many times—clouds of crows that swept down to the fields to dig for seeds or worms—but this was a huge raven, and the sight of it was enough to freeze my blood.

“Away with you, bird,” I said, picking up a small piece of red brick and throwing it at the creature. I missed, but it was enough to send the raven flapping noisily into the sky, a black smear against the lightening heavens. “So you’re scared of birds now, Osric?” I muttered, shaking my head as I crested the hill and made my way through stalks of pink thrift and cushioning sea campion down to the shore. A damp mist had been thrown up to blanket the dunes and shingle, and a flock of screeching gulls passed overhead, tumbling down into the murk, leaving behind them a wake of noise. I jumped across three rock pools full of green weed, the small bladders floating at the surface, then onto my fishing rock, where I knocked a limpet into the sea with the butt of my rod before unwinding the line.

After the time it takes to put a keen edge on a knife, nothing had taken the hook, and I thought about trying another spot where I had once pulled in a rough-skinned fish as long as my leg with wicked, sharp teeth. It was then that I caught a strange sound amid the rhythmic breathing of the surf. I wedged the rod in a crevice, the line still in the sea, and scrambled higher up the rocks above the shingle. But I saw nothing other than the sea-stirred vapor, which seemed alive, like some strange beast writhing before me, concealing and revealing the ocean time and again. I heard only the shrieks of white gulls and the breaking waves and was about to jump down when I heard the strange sound again.

This time I froze like an icicle. My muscles gripped my bones rigid. The breath caught fast in my chest, and cold fear crept up my spine, prickling my scalp. The thin hollow note of a horn sounded again, and then came the rhythmic slap of oars. As if conjured from the spirit world, a dragon emerged, a wooden beast with a belly of clinkered strakes that flowed up into its slender neck. The monster’s head was set with faded red eyes, and I wanted to run but was stuck to the rock like the limpets, fixed by the stare of a great bearded warrior who stood with one arm around the monster’s neck. His beard parted, revealing a malicious smile, then the boat’s keel scraped up the shingle with a noise like thunder, and men were jumping from the ship, sliding on the wet rocks and falling and splashing into the surf. Guttural voices echoed off the rocks behind me, and my bowels melted. Another dragon ship must have beached farther down the shore beyond Hermit’s Rock. Men with swords and axes and round painted shields stepped from the mist, their war gear clinking noisily to shatter the unnatural stillness. They gathered around me like wolves, pointing east and west, their hard voices rousing shrieks from gulls overhead. I mumbled a prayer to Christ and His saints that my death would be quick as the warrior from the ship’s prow stepped up and grabbed my throat. He shoved me at another heathen, who gripped my shoulder with a powerful hand. This one wore a green cloak fastened with a silver brooch in the shape of a wolf’s head. I saw the iron rings of a mail shirt, a brynja, beneath the cloak, and I retched.

Now, after all these years, I might essay a few untruths. I doubt any still live who could prove my words false. I could say that I stuck out my chest and took a grip on my fear. That I did not piss myself. But who would believe me? These outlanders leaping from their dragons were armed and fierce. They were warriors and grown men. And I was just a boy. A strange and frightening magic fell across me then. The outlanders’ sharp language began to change, seemed to melt, the percussive clipped grunts becoming a stream of sounds that were somehow familiar. I swallowed some of the fear, my tongue beginning to move over those noises like water over pebbles, awakening to them, and I heard myself repeating them until they became no longer just noises but words. And I understood them.

“But look at his eye, Uncle!” the man with the wolf brooch said. “He is marked. Ódin god of war has given him a clot of blood for an eye. On my oath, I feel the All-Father breathing down my neck.”

“I agree with Sigurd,” another said, his eyes slits of suspicion. “The way he appeared in the mist was not natural. You all saw it. The vapor became flesh! Any normal man would have run from her.” He pointed to the ship with its carved dragon’s head. “But this one stood here as if he was . . . as if he was waiting for us. I want no part in his death, Sigurd,” he finished, shaking his head.

I prayed they would not see the fishing rod in the crack in the rock, and I hoped the mackerel were still asleep, for mackerel fight like devils and if one took my hook, the line would jump and the heathens would see me for what I was.

“I can help you,” I spluttered, buoyed suddenly by the hope that the outlanders were lost, blown off course on the way to who knew where.

Copyright © 2012 by Giles Kristian.

What an awesome trailer!