So there is this quote by Harry Emerson Fosdick that says:

“He who knows no hardship will know no hardihood. He who faces no calamity will need no courage. Mysterious though it is, the characteristics in human nature which we love best, grow in a soil with a strong mixture of troubles.”

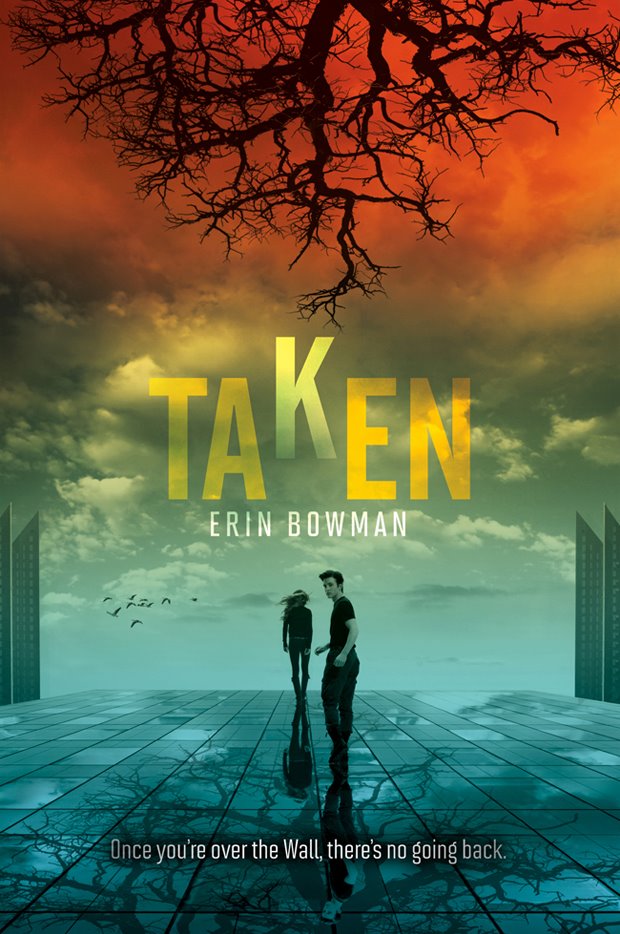

Now, I don’t know how many of you even know who Harry is (FYI – An American pastor from the early 1900’s who later went on to establish the AA movement as well as write a number of MG books for boys under the pen name Harry Castlemon.) or why exactly this has anything to do with Erin Bowman’s novel “Taken”, but I assure you…there is a method to my madness.

Show of hands, who here has seen M. Night Shyamalan’s “The Village?” How many of you liked it? (I’m going to take a wild guess and say not too many of you. Am I right?) Me? It still holds a place as one of my top 15 movies. But probably NOT for the reasons you would think. I enjoy the excitement of an epic twist as much as the next girl, but I CRAVE the reactions of human response.

“The characteristics in human nature which we love best, grow(n) in a soil with a strong mixture of troubles.”

In “The Village” the characters are (unknowingly) trapped inside a colony that lacks the perks of modern technology. (Aka..you better go hand churn your butter or your toast is going to be crazy dry.) They also bear the weight of imminent threat. (Evil beings that live in the surrounding forest thwarting any ideals of escape.)

“Taken” is remarkably similar to “The Village” in its core structure. A) Claysoot is void of anything modern. (The chances of you finding a lightbulb? Zero.) B) They are surrounded by a wall. (Though it’s not a forest the same danger applies. Cross it and die.)

The biggest difference (and what ultimately makes Taken much more interesting) is they way in which one simple deception can ignite the curiosity of not one but three different societies.

In Claysoot…boys disappear at the age of 18. Or at least, they are supposed to.

Which makes “Taken” (much like “The Village”) a sociological experiment on crack. Brought to you courtesy of Erin Bowman. It will make you question human natures complacency in the face of predictability. In other words..do we do what we do, because we do what we’ve always done? (Say that five times fast.)

There are boys—but every one of them vanishes at midnight on his eighteenth birthday. The ground shakes, the wind howls, a blinding light descends . . . and he’s gone.

They call it the Heist.

Gray Weathersby’s eighteenth birthday is mere months away, and he’s prepared to meet his fate—until he finds a strange note from his mother and starts to question everything he’s been raised to accept: the Council leaders and their obvious secrets, the Heist itself, and what lies beyond the Wall that surrounds Claysoot—a structure that no one can cross and survive.

Climbing the Wall is suicide, but what comes after the Heist could be worse. Should he sit back and wait to be taken—or risk everything on the hope of the other side?

Chances are (unless you live under a rock) you have seen this book by now and have been privy to the horrible reviews it has been getting. And while I can appreciate the wide range of people’s taste (we can’t all like the same thing..that would make for a boring world) I can say that I was a tad shocked by the hostility of some of them. (I usually reserve that type of hostility for cliffhangers.)

When it comes right down to it, yes, there were some very “convenient” moments inside “Taken.” Moments that could have easily morphed into something brilliant if the inspiration had struck, but it didn’t, and that’s life. Most books these days have at least one or two of these “throw away” plot lines, and if we are honest with ourselves (as readers) convenience can be overlooked for originality. And “Taken” (if nothing else) was teeming with brilliant possibilities for a bright dystopian future.

But let’s back up and start at the beginning. With Gray, the protagonist of this story.

Gray is the perfect character for dystopic purposes. He is unafraid to test boundaries. Ask question. Believe in the possibility of more. He is also stubborn as a mule. He makes rash decisions on a fairly regular basis, and it takes a gun to his head before he realizes that maybe trusting everyone isn’t such a wise decision. He is unfailingly human. He bleeds. He hurts. He doubts. All traits that combine to make a truly fascinating character who found himself wrapped up in extraordinary circumstances.

As for the extraordinary circumstances…they are fairly complex. The name of the game in Taken is “shift.” Every chapter asks a question and provides an answer, but piecing them together in the correct order is the challenge. Good is mistaken for Evil, and Right is sometimes Wrong. When you have THAT sorted out, the story falls into place in perfect discombobulated harmony. (I promise…that will make sense if you choose to read the book.)

But don’t fret too much. Despite its complex plot (which I’m trying desperately not to giveaway) it is an incredibly quick read (4 hours at the most.) and ends on a pretty good note. (Not a cliffhanger, but plenty of intrigue.)

It DOES fall short in the overall scheme of thing (aka the wide world of dystopian literature) but it’s not gracing the bottom of the barrel. Like I said above, it has the “makings” of something great. I say take a chance, but waiting until your TBR is clear of some of your “must reads” first. Maybe put it on a shelf until #2 comes out.

Until then…Happy Reading my fellow Kindle-ites and remember: “Being stubborn can be a good thing. Being stubborn can be a bad thing. It just depends on how you use it.” – Willie Aames

| Rating Report | |

|---|---|

| Plot | |

| Characters | |

| Writing | |

| Pacing | |

| Overall: | 3.4 |

I really liked that movie (The Village). I can’t wait to read Taken. It sounds right up my alley. I have to say…what an awesome cover. I love covers. 🙂

I swear…I’ve watched The Village like 200 times. I love the porch scene. 😉

And the cover… LUST!! It is just so beautiful.