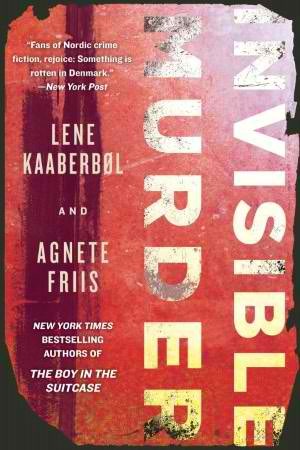

Invisible Murder by Lene Kaaberbol & Agnete Friis

The second installment in the bestselling Danish crime series starring Red Cross nurse Nina Borg, following Fall 2011’s New York Times–bestselling The Boy in the Suitcase

In the ruins of an abandoned Soviet military hospital in northern Hungary, two impoverished Roma boys are scavenging for old supplies or weapons they could sell on the black market when they find more than they ever anticipated. The resulting chain of events threatens to blow the lives of a frightening number of people into bits and pieces.

In this feverishly anticipated follow-up to 2011’s critically acclaimed The Boy in the Suitcase, Danish Red Cross nurse Nina Borg doesn’t realize she is putting life and family on the line when she tries to treat a group of sick Hungarian gypsies who are living illegally in a Copenhagen garage. Nina has unwittingly thrown herself into a deadly nest of the unscrupulous and the desperate, and what is at stake is much more terrifying than anyone had realized.

EXCERPT

PROLOGUE:

NORTHERN HUNGARY

“Maybe we’ll find a gun,” Pitkin said, aiming his finger at the guardhouse next to the gate. “Pchooooof!”

“Or even a machine gun,” Tamás said, firing an imaginary weapon from his hip. “Ratatatatatatata!”

“Or a tank!”

“They took all the tanks with them,” Tamás said with a sudden, inappropriate realism.

“A grenade then,” Pitkin tried. “Don’t you think they might have forgotten a grenade somewhere?”

“Well, you never know,” Tamás said to avoid totally deflating his friend’s hopes.

Darkness had just fallen. It had been a wet day, and the smell of rain and damp still hung in the air. If it had still been raining, they would probably not have come. But here they were, he and Pitkin, and even though he didn’t really believe in the miraculous guns, machine guns, or grenades, excitement was fizzing inside him, as if his stomach was a shook-up bottle of soda.

There was a fence around the old military camp, but the lone night watchman had long since given up trying to defend it against the hordes of scrap thieves and junk dealers. He stayed in his boxy little guardhouse now, the only building still boasting such amenities as electricity and water, and watched TV on a little black-and-white television set that he took home with him every morning at the end of his shift. One time he had actually fired a shot at the Rákos brothers when they had tried to steal his TV, and that had earned him a certain amount of respect. Now there was a sort of uneasy détente: The guard’s territory extended from the guardroom to the gate and the area immediately around it, in other words the front gate and the section of fence facing the road; even the most enterprising of the local thieves did not go there. But the rest was no-man’s land, and anything remotely portable was now long gone—even the fence itself. György Motas had stolen long sections of it for his dog run.

Tamás knew perfectly well that the chances of finding any valuable leftovers were miniscule. But what else was there to do on a warm spring night if you were stony broke? And although Pitkin mostly talked like an eight-year-old, he was almost eighteen and stronger than most. They might just luck onto something that others had left behind because it was simply too heavy.

They ducked under the fence. That fizzing, tingling feeling of being somewhere forbidden grew, and Tamás grinned in the darkness. Around them stood the bare concrete walls of what had been the officers’ mess, shower stalls, workshops, and offices, looking like abandoned movie sets. Windows and doors were long gone and put to good use elsewhere, just like rafters and roof tiles, radiators, water pipes, faucets, sinks, and old toilet bowls. The wooden barracks where the rank-and-file Soviet soldiers had once slept were totally gone, removed board by board so that only the concrete foundation remained. The largest and most intact building was the old infirmary, which at three stories towered over the rest of the place, like a castle surrounded by farmhouses. For several years after the Russians had gone home, it had served as a clinic for the locals, run by one of the various Western aid organizations. But by and by all the English-speaking doctors and nurses and volunteers had disappeared, and the scavengers had descended like a swarm of grasshoppers. Those first few weeks had been extremely lucrative—Attila found a steel cabinet full of rubbing alcohol, and Marius Paul unloaded three microscopes in Miskolc for almost 50,000 forints – but now even the infirmary was just a chicken carcass picked clean of every last shred of meat. All the same, this was where Tamás and Pitkin were headed.

Tamás slid in through the empty door hole, turning on his flashlight to see where he was going. Patches of gray-blue moonlight filtered down from the cracks in the roof, but otherwise the darkness was thick and dank and impenetrable.

“Boo!” yelled Pitkin behind him, loud enough to make him jump. The sound echoed inside the walls, and Pitkin laughed. “Did I scare you?” he asked.

Tamás just grunted. Sometimes Pitkin was just too childish.

There were still torn scraps of yellowing linoleum on the floor and remnants of green paint on the walls. Tamás shone the light up into the stairwell. Three floors up, he could make out a patch of night sky; even here the swarm had begun to consume the tiles. The basement was inaccessible—for some reason the Russians had gone to the trouble of sealing it off by the simple expedient of pouring a load of wet concrete into the stairwells, both here and at the northern end of the building.

Pitkin peered down the deserted corridor. He snatched the flashlight out of Tamás’s hand, holding it as if it were a gun, and darted across to the first doorway. “Freeze!” he yelled, pointing the beam of light into the empty hospital ward.

“Shhh,” Tamás said. “Do you want to bring the guard down on us?”

“No chance. He’s snoring away in front of his TV, like he always is.” But Pitkin lost a little of his action-hero swagger all the same. “Whoah,” he said. “Something happened here…”

He was right. The light from the flashlight raked the flaking green walls to reveal a massive gcrack in the brickwork below the window. There was more debris than usual on the floor—parts of the ceiling had caved in, and swaths of plaster and old paint were hanging down in strips. Tamás suddenly had the uncomfortable feeling that the floor above them might collapse at any minute, turning him and Pitkin into the meaty filling of a concrete sandwich. But then he caught sight of something that made his greed unfurl like wings.

“There,” Tamás said. “Shine the light over there again.”

“Where?”

“Over by the window. No, the floor…”

It might have been normal decay, or one of the small tremors that had formed ripples in their coffee cups at home. Whatever the cause, the old infirmary had taken a big step closer to total ruin. The crack in the wall had caused part of the floor to tumble into the basement below—the basement that had been inaccessible since the day the Russians had sealed both entrances with concrete.

Pitkin and Tamás looked at each other.

“There must be tons of stuff down there,” Tamás said.

“All kinds of stuff,” Pitkin said. “Maybe even a grenade…”

Strictly speaking, Tamás would rather find a couple of microscopes like the ones that had proved such a windfall for Marius Paul.

“I can fit through there,” Tamás said. “Give me the light.”

“I want to go down, too,” Pitkin said.

“Yeah, yeah. But we have to do it one at a time.”

“Why?”

“You idiot. If we both jump down there, how are we going to get back out again?”

They didn’t have a rope or ladder, and Pitkin reluctantly conceded Tamás’s point. So it was just Tamás who sat down at the edge of the gap and cautiously stuck his feet and legs through the irregularly shaped hole. He hesitated a bit.

“Hurry up. Or I’ll do it!” Pitkin said.

“Okay, okay. Just a second!”

Tamás didn’t want Pitkin to think he was chicken, so he pushed himself forward a little and slipped through the hole. As he began to fall, there was a sharp stab of pain in his arm.

“Ow!” he cried.

He landed crookedly, on a heap of rubble from the collapsed ceiling, but although it jarred his bones, the sharper pain still came from his left upper arm.

“What’s wrong?” Pitkin asked from above.

“I cut myself on something,” Tamás said. He could feel the blood soaking his sleeve. God damn it. A 10-inch wooden splinter was embedded in his flesh, just below his armpit. He pulled it out, but it left a jagged tear that seemed to throb increasingly the longer he stood waiting for it to subside.

“Well, is there anything down there?” Pitkin asked impatiently, his concern for Tamás’s wellbeing already forgotten.

“Can’t see a thing, can I? Pass me the light.”

Pitkin lay down on the floor and lowered the flashlight through the hole. Tamás was just able to reach it. Luckily the ceilings in the basement weren’t as high as in the rest of the infirmary.

It was obvious right away that they had struck pure gold. Everything was still there, just like he’d hoped. Two hospital gurneys, a steel cabinet, a shitload of instruments—although he didn’t see anything that looked like a microscope. The radiators and faucets and sinks were intact, there were books and vials and bottles on the shelves and in the cabinets, and in the corner there was a standing scale like the school nurse’s, with weights you slid back and forth until they balanced. And this was just the first room. The thought of what that alone might be worth almost made Tamás forget the pain in his arm. If they could get it all out of there before anyone else discovered their treasure trove, of course.

“Any weapons?” Pitkin asked.

“I don’t know.”

He opened the door to the hallway – and there were still doors down here. Thick, heavy, steel doors that squeaked when he pushed on them. Tamás moved quickly down the corridor, opening them one by one, shining his light into the rooms beyond. This one was obviously an operating theatre, with huge lamps still hanging from the ceiling and a stainless-steel operating table in the middle. Next came a storage room full of locked cabinets. Tamás’s heart beat faster when he realized there were still whole box-loads of drugs in there behind the glass doors. Depending on what they were, and how they’d held up, those could be worth even more than microscopes.

But it was the next room that made him stop and stare so intensely that Pitkin’s impatient yells faded completely from his consciousness.

At some point it must have hung from the ceiling, but tremors or general decay had loosened the fat bolts, and at some point the whole thing had come crashing down onto the cracked tile floor. The sphere had been ripped off the arm in the fall and was lying by itself, cracked and scratched, its yellow paint reminding him a little of the bobbing naval mines he’d seen in movies. He cautiously stretched out his hand and touched it, very, very gently. It felt warm, he thought. Not scalding, just skin temperature, as though it were alive. He could still make out the warning label, black against the yellow, despite the scratches and the concrete dust.

He took a couple of steps back. The light from his flashlight had grown noticeably dimmer. The battery must be running low. He was going to have to get back to the hole while he could still see anything at all. On the way he smashed open the glass door of one of the medicine cabinets, blindly snatching a few jars and boxes. Pitkin was yelling again, more audibly now that Tamás was closer to the hole.

Tamás’s mind was working at fever pitch. It was as if he could suddenly see the future, so clearly that everything he would have to do fell neatly into place, almost as if he had already done it and was remembering it, rather than planning it. Yes. First we will have to do this. And then this. And then if I ask …

“Did you find a grenade?” Pitkin interrupted his train of thought, less loudly now that he could see Tamás was back.

Tamás looked up though the hole. Pitkin’s face hung like a moon in the middle of the darkness, and Tamás could feel a strange, involuntary grin tugging at his own mouth, turning it as wide as a frog’s.

“No,” he said breathlessly, still seeing in his mind’s eye the cracked yellow sphere with its stark, black warning sign.

“Well then, what? What did you find?”

“It’s better than a grenade,” he said. “Much, much better …”

APRIL

Lately, Skou-Larsen had been thinking quite a lot about his imminent death.

When he got out of bed in the mornings, he felt a certain amount of resistance as he inhaled, as if breathing was no longer something that could be taken for granted. He had to exert himself. The pain in his joints had long ago turned into a constant background noise that he barely noticed, even though it wore him out.

It was no wonder, he supposed. His originally quite serviceable body had after all been in use since 1925, and some degree of decay was only to be expected. What bothered him wasn’t so much the aches and the shortness of breath in itself; it was what they signified.

He looked across the shiny white conference table at the lawyer sitting opposite him, duly armed with professional-looking case files and what was presumably the latest in fashionable eyewear.

“I just want to be sure my wife will have the support she needs once I’ve passed on,” Skou-Larsen said. That was what he’d decided to call it, passing on. There was something graceful about the expression, he thought. It implied a smooth and civilized progress toward a destination, and for a moment he imagined himself aboard a tall ship, sails burgeoning in the breeze, flags flying, and the flash of sunlight on rippling blue waves as the land of the living fell away behind him. He liked the image. It obscured the clinical reality of death, so he didn’t need to think about fluid in his lungs, morphine drips and failing organs, lividity, and the moribund blood slowly congealing in his shriveled veins.

The lawyer nodded. Mads Ahlegaard, his name was. Skou-Larsen had picked him because he was the son of the Ahlegaard who had always been his lawyer. But now Ahlegaard the Elder was off strolling around a golf course a little ways outside Marbella in southern Spain, and Skou-Larsen was having to make do with this younger and somewhat less confidence-inspiring version.

“I can certainly understand that, Jørgen,” the Ahlegaard the Younger said, nodding again to add emphasis to his words. “But exactly what type of support do you believe your wife needs?”

Skou-Larsen felt a growing sense of frustration. He had already explained all of this.

“I’ve always been the one who looked after things,” he said. “All the administrative and financial transactions, and… well, a lot of other things, too. I want Claus… that is, our son… to play a role in the future.” The future. There. That was also a tidy, optimistic way of referring to it. The future—after the worms had had their way with him and moved on to their next feast.

“Yes, I’m sure he’ll be a great support for her.”

Skou-Larsen felt the muscles in his jaw and around his eyes tightening. This young man on the other side of the table simply refused to understand, sitting there in his shirtsleeves, with his jacket draped over the back of his chair like some high school student. How old could he be? Not more than thirty-five, surely. Otherwise he would have learned by now that not everyone appreciates being addressed by their first name, in that overly familiar manner.

“But what if she doesn’t ask him? What if she just … does something? She has no business experience, and I don’t think she is a very good judge of character. She is a lot more fragile than people imagine. Couldn’t we … take precautions?” Skou-Larsen asked.

“Such as?”

“If my son had power-of-attorney, for example. Then he would be in charge of the financial matters and everything having to do with the house.”

“Jørgen, your wife is an adult, with the right to make her own decisions. Besides, the house is in her name.”

“I know! That is exactly what is wrong!”

Ahlegaard Jr. pushed his thin, square titanium glasses higher up his nose with a sunburned index finger. “On the contrary,” he said. “This will make things so much easier for her taxwise. Estate duties are no joke.”

“That’s as may be. But it also made it all too easy for her to borrow 600,000 kroner from the bank, and then spend it all on some Costa del Con-Artist project that I’m sure never existed outside the brochure’s glossy pictures. Can’t you understand I’m worried about her?”

“Jørgen, I think you should discuss this with her. Maybe both you and Claus should have a talk with her. Formally, the house is hers, and she is allowed to do whatever she wants with it. Legally and ethically, there is no document I can set up for you that will change that. Unless she is herself in favor of the power-of-attorney idea?”

“She is not,” Skou-Larsen said. He’d tried, but he just couldn’t get through to her.

“No? Well, then…”

The conversation was over. That was clear from the way Ahlegaard gathered up his papers. Skou-Larsen remained seated for another few seconds, but all that did was draw Junior around to his side of the table to shake hands.

“Should I ask Lotte to call you a cab?” he asked.

“No thank you. I have my own car.”

“Really? Such a pain finding a parking spot around here, isn’t it?”

Skou-Larsen slowly stood up. “So, you’re saying that you won’t help me?” he asked glumly.

“We’re always here to help. Just call me if there’s anything we can do and we’ll set up a meeting.”

*

An April shower had just been and gone as Skou-Larsen left the downtown offices of his unhelpful lawyer. In the park across the street, forsythia branches were drooping soddenly over the gravel footpaths, and the narrow tires on passing bicycles hissed wetly on the bike path.

As Ahlegaard expected, he had indeed had a hard time finding a parking spot close to the law firm’s offices on Gothersgade, and Skou-Larsen was quite winded by the time he made it back to the parking structure on Adelgade where he had finally managed to park his beloved Opel Rekord. Perhaps that was why he didn’t notice the black Citroën.

“Hey, watch it, buddy!”

He felt someone grab his shoulder, causing him to teeter backwards and fall. Lying on the asphalt, he saw a car tire, shiny from the rain, pass within centimeters of his face. Grime from the wet road struck his cheek like hail.

“Are you okay?”

The car was gone. Skou-Larsen found himself staring up at a sweaty, young man in a tight-fitting neon-green racing jersey and bike shorts, unable to answer his rescuer’s question.

“Should I call an ambulance?”

He shook his head mutely. No, no ambulance. “I’ll just go home,” he finally managed to say. Helle was waiting for him and he didn’t want her to worry.

He got up, thanked the neon-colored bike messenger, found his car keys, safely reached his Opel, and sat down in the driver’s seat. Nothing had happened, he told himself, and then he repeated it to be on the safe side. Nothing whatsoever had happened.

But driving home, he couldn’t stop thinking about what might have happened. Not bit by bit, dragging out over months and maybe years, but now, in a single, raw instant, splat against the asphalt like a blood-filled mosquito on a windshield.

One could pass away like that, too.