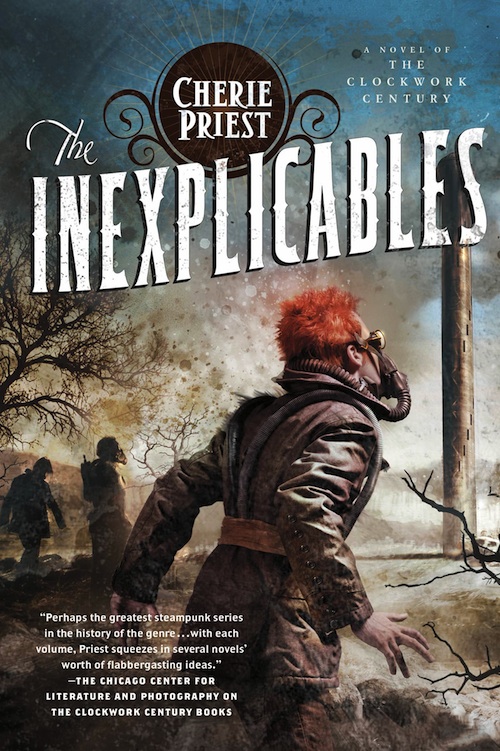

Rector “Wreck ‘em” Sherman was orphaned as a toddler in the Blight of 1863, but that was years ago. Wreck has grown up, and on his eighteenth birthday, he’ll be cast out out of the orphanage.

Rector “Wreck ‘em” Sherman was orphaned as a toddler in the Blight of 1863, but that was years ago. Wreck has grown up, and on his eighteenth birthday, he’ll be cast out out of the orphanage.

And Wreck’s problems aren’t merely about finding a home. He’s been quietly breaking the cardinal rule of any good drug dealer and dipping into his own supply of the sap he sells. He’s also pretty sure he’s being haunted by the ghost of a kid he used to know—Zeke Wilkes, who almost certainly died six months ago. Zeke would have every reason to pester Wreck, since Wreck got him inside the walled city of Seattle in the first place, and that was probably what killed him. Maybe it’s only a guilty conscience, but Wreck can’t take it anymore, so he sneaks over the wall.

The walled-off wasteland of Seattle is every bit as bad as he’d heard, chock-full of the hungry undead and utterly choked by the poisonous, inescapable yellow gas. And then there’s the monster. Rector’s pretty certain that whatever attacked him was not at all human—and not a rotter, either. Arms far too long. Posture all strange. Eyes all wild and faintly glowing gold and known to the locals as simply “The Inexplicables.”

In the process of tracking down these creatures, Rector comes across another incursion through the wall—just as bizarre but entirely attributable to human greed. It seems some outsiders have decided there’s gold to be found in the city and they’re willing to do whatever it takes to get a piece of the pie unless Rector and his posse have anything to do with it.

EXCERPT

One

Rector “Wreck’em” Sherman was delivered to the Sisters of Loving Grace Home for Orphans the week it opened, on February 9, 1864. His precise age was undetermined, but estimated at approximately two years. He was filthy, hungry, and shoeless, wearing nothing on his feet except a pair of wool socks someone, somewhere, had lovingly knitted for him before the city went to hell. Whether she had been mother or nursemaid, governess or grandmother, no one knew and no one ever learned; but the child’s vivid red hair, pearl white skin, and early suggestions of freckles implied rather strongly that he was no relation to the Duwamish woman who brought him to the shelter. She’d carried him there, along with another child who did not survive the month. Her own name was lost to history, or it was lost to incomplete records only sometimes kept in the wake of the Boneshaker catastrophe.

The little boy who lived, the one with hair the color of freshly cut carrots, was handed over to a nun with eyes too sad for someone so young and a habit too large for someone so small. The native woman who toted Rector told her only his name, and that “There is no one left to love him. I do not know this other boy, or what he is called. I found him in the bricks.”

For a long time, Rector did not talk.

He did not babble or gesture or make any sound at all, except to cry. When he did, it was a strange cry—all the nuns agreed, and nodded their accord sadly, as though something ought to be done about it—a soft, hooting sob like the desolate summons of a baby owl. And when the dark-haired boy who’d been his circumstantial companion passed away from Blight poisoning, or typhoid, or cholera, or whatever else ravaged the surviving population that week . . . Rector stopped crying as well.

He grew into a pallid, gangly thing, skinny like most of the refugees. At first, people in the Outskirts had bartered for what they could and took ships and airships out into the Sound to fish; but within six months, Blight-poisoned rainwater meant that little would grow near the abandoned city. And many of the children— the ones like Rector, lost and recovered—were stunted by the taint of what had happened. They were halted, slowed, or twisted by the very air they’d breathed when they were still young enough to be shaped by such things.

All in all, Rector’s teenage condition could’ve been worse.

He could’ve had legs of uneven lengths, or eyes without whites—only yellows. He might’ve become a young man without any hair, even eyebrows or lashes. He might’ve had far too many teeth, or none at all. His spine might have turned as his height overtook him, leaving him lame and coiled, walking with tremendous difficulty and sitting in pain.

But there was nothing wrong with him on the outside.

And therefore, able-bodied and quick-minded (if sometimes mean, and sometimes accused of petty criminal acts), he was expected to become a man and support himself. Either he could join the church and take up the ministry—which no one expected, or even, frankly, wanted—or he could trudge across the mud flats and take up a job in the new sawmill (if he was lucky) or at the waterworks plant (if he was not). Regardless, time had run out on Rector Sherman, specific age unknown, but certainly—by now—at least eighteen years.

And that meant he had to go.

Today.

Sometime after midnight and long before breakfast—the time at which he would be required to vacate the premises—Rector awoke as he usually did: confused and cold, and with an aching head, and absolutely everything hurting.

Everything often hurt, so he had taken to soothing the pain with the aid of sap, which would bring on another pain and call for a stronger dose. And when it had all cycled through him, when his blood was thick and sluggish, when there was nothing else to stimulate or sedate or propel him through his nightmares . . . he woke up. And he wanted more.

It was all he could think about, usurping even the astonishing fact that he had no idea where he was going to sleep the next night, or how he was going to feed himself after breakfast.

He lay still for a full minute, listening to his heart surge, bang, slam, and settle.

This loop, this perpetual rolling hiccup of discomfort, was an old friend. His hours stuttered. They stammered, repeated themselves, and left him at the same place as always, back at the beginning. Reaching for more, even when there wasn’t any.

Downstairs in the common room the great grandfather clock chimed two—so that was one mystery solved without lifting his head off the pillow. A minor victory, but one worth counting. It was two o’clock in the morning, so he had five hours left before the nuns would feed him and send him on his way.

Rector’s thoughts moved as if they struggled through glue, but they gradually churned at a more ordinary pace as his body reluctantly pulled itself together. He listened over the thudding, dull bang of his heart and detected two sets of snores, one slumbering mumble, and the low, steady breaths of a deep, silent sleeper.

Five boys to a room. He was the oldest. And he was the last one present who’d been orphaned by the Blight. Everyone else from that poisoned generation had grown up and moved on to something else by now—everyone but Rector, who had done his noble best to refuse adulthood or die before meeting it, whichever was easier.

He whispered to the ceiling, “One more thing I failed at for sure.” Because, goddammit, he was still alive.

In the back of his mind, a shadow shook. It wavered across his vision, a flash of darkness shaped like someone familiar, someone gone. He blinked to banish it, but failed at that, too.

It hovered at the far edge of what he could see, as opposed to what he couldn’t.

He breathed, “No,” knowing that the word had no power. He added, “I know you’re not really here.” But that was a lie, and it was meaningless. He didn’t know. He wasn’t sure. Even with his eyes smashed shut like they were welded that way, he could see the figure outlined against the inside of his lids. It was skinny like him, and a little younger. Not much, but enough to make a difference in size. It moved with the furtive unhappiness of something that has often been mocked or kicked.

It shifted on featherlight feet between the boys’ beds, like a feral cat ready to dodge a hurled shoe.

Rector huddled beneath his insufficient blankets and drew his feet against himself, knees up, panting under the covers and smelling his own stale breath. “Go away,” he commanded aloud. “I don’t know why you keep coming here.”

Because you’re here.

“I didn’t hurt you.”

You sent me someplace where you knew I’d get hurt.

“No, I only told you how to get there. Everything else was you. It was all your own doing. You’re just looking for someone to blame. You’re just mad about being dead.”

You murdered me. The least you could do is bury me.

The ghost of Ezekiel Wilkes quivered. It came forward, mothlike, to the candle of Rector’s guilt.

You left me there.

“And I told you, I’ll come find you. I’ll come fix it, if I can.”

He waited until his heart had calmed, and he heard only the farts, sniffles, and sighs that made up the nighttime music of the orphans’ home. He moved his legs slowly beneath the blanket until his feet dangled off the edge of the flat straw mattress.

The air on the other side of the blanket was cold, but no colder than usual; it seeped through the holes in his socks and stabbed at the soft places between his toes. He flexed them and shivered. His boots were positioned just right, so he could drop down into them without even looking. He did so, wriggling his ankles until he’d wedged his feet securely into the worn brown leather, and he did not bother to reach down and tie their laces. The boots flopped quietly against the floor as he extracted himself from the bedding and reached for the jacket he’d left over the footboard. He put it on and stood there shaking in the frigid morning darkness. He blew on his hands to briefly warm them, then took a deep breath that he held inside to stretch his chest and urge himself more fully awake.

He was already wearing gray wool pants and a dull flannel shirt. He slept in them, more often than not. It was entirely too cold in the orphan’s home to sleep in more civilized, sleep-specific attire—even in what was considered summer almost anywhere else in the country.

In the Northwest, they called this time of year the June Gloom.

Until the end of July, the clouds always hung low and close and cold. Everything stayed damp even if it wasn’t raining, and usually, it was. Most of the time it wasn’t a hard rain, but a slow, persistent patter that never dried or went away. The days didn’t warm, and at least once a week there was frost in the morning. People grumbled about how It’s never usually like this, but as far as Rector could recall, it was never usually any different. So on the third of June in 1880, Rector’s teeth chattered and he wished for something warmer to take with him.

Cobwebs stirred in the corners of Rector’s mind, reminding him that something dead was prone to walking there. It kept its distance for now—maybe this was one of the benefits to being unwillingly sober and alert, but Rector didn’t want to count on it. He knew too well how the thing came and went, how it hovered and accused, whether he was waking or sleeping.

And it was getting stronger.

Why was that? He had his theories.

The way Rector saw it, he was dying—killing himself slowly and nastily with sap, the potent, terrible drug made from the poisoned air inside the city walls. No one used it more than a year or two and lived, or lived in any condition worth calling that. Rector had no illusions. He didn’t even mind. If anything, his death would factor nicely into his plan to evade responsibility in the long term, even if he was being forced to address it in the short term.

Dead was easier than alive. But the closer he got to being dead, the nearer his dead old chums were able to get to him. It wasn’t fair, really—it was hard to fight with a ghost when he wasn’t yet a ghost himself. He suspected it’d be a much simpler interaction when he and Zeke were both in a position to scare the bejeezus out of each other, or however that worked.

He exhaled hard, and was dimly glad to note that he could not see his breath. This morning was not as cold as some.

And, dammit all, he was almost out of sap.

In the bottom of his left coat pocket, Rector had constructed a secret corner pocket, between the two threadbare layers that made up his only outerwear. Down there, nestled in a crinkly piece of waxed wrapper, a folded slip held a very small amount of the perilous yellow dust.

Rector resisted the urge to seize it, lest the added noise from the paper summon someone’s half-asleep attention. Instead, he comforted himself with the knowledge that it (still, barely) existed, and he jammed a black knit hat down over his ears.

He surveyed the room.

It was too dark to see anything clearly. But he knew the layout, knew the beds.

Seizing his own blanket by the corner, he folded it in half and laid out his few personal effects: One extra pair of socks, in no better shape than the ones he wore already. One additional shirt, neither smelling fresher nor appearing newer than what he had on. A box of matches. An old gas mask, soft from years of being worn by somebody else, but still working fine. Rector didn’t have any extra filters, but the ones in the mask were new. He’d stolen them last week, just like he stole everything else he’d ever owned: on a whim, or so he’d thought at the time. In retrospect, the idea might’ve already been brewing, bubbling on a back burner where he hadn’t noticed it yet.

He reached underneath the mattress, to a spot where the fabric covering had rubbed itself threadbare against the slats that held it above the floor. Feeling around with his left hand, he retrieved a small bag he’d stitched together from strips of a burlap bag that once held horse feed. Now it held other things, things he didn’t particularly want found, or taken away.

He added this pouch to the stash on the bed and tied up the corners of the blanket. The blanket wasn’t really his to commandeer, but that wouldn’t stop him. The Home was throwing him out, wasn’t it? He figured that meant that the muttering nuns and the cadaverous priest practically owed him. How could they expect a young man to make his way through life with nothing but the clothes on his back? The least they could do is give him a blanket.

Slipping his hand inside the makeshift bag’s loops, he lifted it off the bed and slung it over one shoulder. It wasn’t heavy.

He stopped in the doorway and glared for the last time into the room he’d called “home” for more than fifteen years. He saw nothing, and he felt little more than that. Possibly a twinge, some tweak of memory or sentiment that should’ve been burned out of operation ages ago.

More likely, it was a tiny jolt of worry. Not that Rector liked the idea of worrying any better than he liked the idea of nostalgia, but the last of his sap would take care of it. All he needed was a safe, quiet place to fire up the last of the precious powder, and then he’d be free again for . . . Another few hours at most, he thought sadly. Need to go see Harry. This won’t be enough.

But first things first.

Into the hall he crept, pausing by the stairs to loosely, hastily tie his boots so they wouldn’t flap against the floor. Down the stairs he climbed, listening with every step for the sound of swishing nun robes or insomniac priest grumblings. Hearing nothing, he descended to the first floor.

A candle stub squatted invitingly on the end table near Father Harris’s favorite reading chair beside the fireplace in the main room. Rector collected the stub and rifled through his makeshift bag to find his matches. He lit the candle and carried it with him, guarding the little flame with the cup of his hand as he went.

Tiptoeing into the kitchen, he gently pushed the swinging door aside. He wondered if there was any soup, dried up for boiling and mixing. Even if it wasn’t anything he wanted to eat, he might be able to barter with it later. And honestly, he wasn’t picky. When food was around, he ate it. Whatever it was.

The pantry wasn’t much to write home about. It was never stocked to overflowing, but it never went empty, either. Someone in some big church far away saw to it that the little outposts and Homes and sanctuaries like these were kept in the bare essentials of food and medicine. It wasn’t a lot—any fool could see this was no prosperous private hospital or sanatorium for rich people—but it was enough to make Rector understand why so many folks took up places in the church, regardless. Daily bread was daily bread, and hardly anybody leftover from the city that used to be Seattle had enough to go around.

“They owe me,” he murmured as he scanned the pantry’s contents.

They owed him that loaf of bread wrapped in a dish towel. It hadn’t even hardened into a stone-crusted brick yet, so this was a lucky find indeed. They owed him a bag of raisins, too, and jar of pickles, and some oatmeal. They might’ve owed him more, but a half-heard noise from upstairs startled Rector into cutting short his plunder.

Were those footsteps? Or merely the ordinary creaks and groans of the rickety wood building? Rector blew out the candle, closed his eyes, and prayed that it was only a small earthquake shaking the Sound.

But nothing moved, and whatever he’d heard upstairs went silent as well, so it didn’t matter much what it’d been. Some niggling accusation in the back of his drug-singed mind suggested that he was dawdling, wasting time, delaying the inevitable; he argued back that he was scavenging in one of the choicest spots in the Outskirts, and not merely standing stock-still in front of an open pantry, wondering where the nuns kept the sugar locked up.

Sugar could be traded for some serious sap. It was more valuable than tobacco, even, and the gluttonous, sick part of his brain that always wanted more gave a little shudder of joy at the prospect of presenting such an item to his favorite chemist.

He remained frozen a moment more, suspended between his greed and his fear.

The fear won, but not by much.

Rector retied his blanket-bag and was pleased to note that it was now considerably heavier. He didn’t feel wealthy by any means, but he no longer felt empty-handed.

Leaving the kitchen and passing through the dining area, he kept his eyes peeled against the Home’s gloomy interior and scanned the walls for more candle stubs. Three more had been left behind, so into his bag they went. To his delight, he also found a second box of matches. He felt his way back to the kitchen, and onward to the rear door. Then with a fumbled turning of the lock and a nervous heave, he stumbled into the open air behind the Home.

Outside wasn’t much colder than inside, where all the fires had died down and all the sleeping children were as snug as they could expect to get. Out here, the temperature was barely brittle enough to show Rector a thin stream of his own white-cloud breath gusting weakly before him, and even this chill would probably evaporate with dawn, whenever that came.

What time was it again?

He listened for the clock and heard nothing. He couldn’t quite remember, but he thought the last number he’d heard it chime was two. Yes, that was right. It’d been two when he awoke, and now it was sometime before three, he had to assume. Not quite three o’clock, on what had been deemed his “official” eighteenth birthday, and the year was off to one hell of a start. Cold and uncomfortable. Toting stolen goods. Looking for a quiet place to cook up some sap.

So far, eighteen wasn’t looking terribly different from seventeen.

Rector let his eyes adjust to the moonlight and the oil lamp glow from one of the few street posts the Outskirts could boast. Between the sky and the smoking flicker of the civic illumination, he could just make out the faint, unsettling lean of the three-story building he’d lived in all his life. A jagged crack ran from one foundation corner up to the second floor, terminating in a hairline fracture that would undoubtedly stretch with time, or split violently in the next big quake.

Before the Boneshaker and before the Blight, the Home had been housing for workers at Seattle’s first sawmill. Rector figured that if the next big quake took its time coming, the Home would house something or somebody else entirely someday. Everything got repurposed out there, after all. No one tore anything down, or threw anything away. Nobody could spare the waste.

He sighed. A sickly cloud haloed his head, and was gone.

Better make myself scarce, he thought. Before they find out what all I took.

Inertia fought him, and he fought it back—stamping one foot down in front of the other and leaving, walking away with ponderous, sullen footsteps. “Good-bye, then,” he said without looking over his shoulder. He made for the edge of the flats, where the tide had not come in all the way and the shorebirds were sleeping, their heads tucked under their wings on ledges, sills, and rocky outcroppings all along the edge of Puget Sound.

The Inexplicables @ 2012 Cherie Priest

Awesome!!!