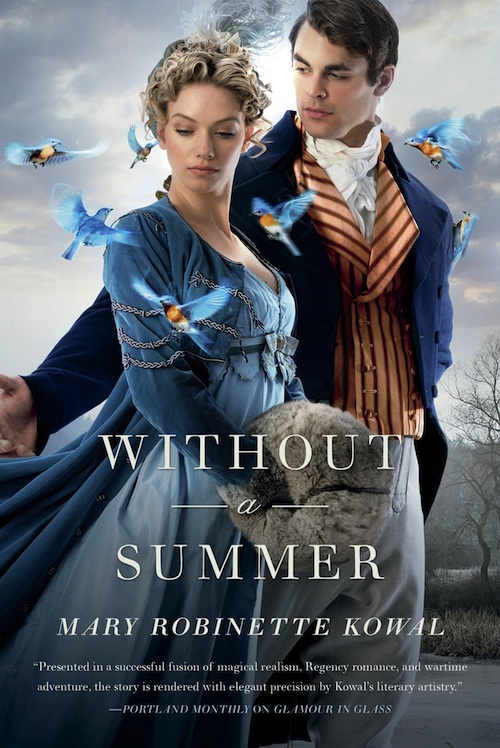

Without A Summer by Mary Robinette Kowal

Publication Date: April 2, 2013

Up-and-coming fantasist Mary Robinette Kowal enchanted fans with award-winning short stories and beloved novels featuring Regency pair Jane and Vincent Ellsworth. In Without a Summer the master glamourists return home, but in a world where magic is real, nothing—even the domestic sphere—is quite what it seems.

Jane and Vincent go to Long Parkmeade to spend time with Jane’s family, but quickly turn restless. The year is unseasonably cold. No one wants to be outside and Mr. Ellsworth is concerned by the harvest, since a bad one may imperil Melody’s dowry. And Melody has concerns of her own, given the inadequate selection of eligible bachelors. When Jane and Vincent receive a commission from a prominent family in London, they decide to take it, and take Melody with them. They hope the change of scenery will do her good and her marriage prospects—and mood—will be brighter in London.

Once there, talk is of nothing but the crop failures caused by the cold and increased unemployment of the coldmongers, which have provoked riots in several cities to the north. With each passing day, it’s more difficult to avoid getting embroiled in the intrigue, none of which really helps Melody’s chances for romance. It’s not long before Jane and Vincent realize that in addition to getting Melody to the church on time, they must take on one small task: solving a crisis of international proportions.

Excerpt

One

Birds and Snow

Jane, Lady Vincent could never be considered a beauty, but possessed of a loving husband and admirable talent, had lived thirty years in the world with only a few events to cause her any true distress or vexation. She was the eldest of two daughters of a gentleman in the neighbourhood of Dorchester. In consequence of her mother’s nerves, Jane had spent the better part of her youth acting as mother to her younger sister, Melody. Her sister had received nature’s full bounty of beauty, with all the charms of an amiable temper. At the age of twenty, it was therefore surprising to find Melody not only unmarried, but without any prospects.

Since Jane’s marriage, she had rarely been to visit her parents, but finding herself there for an extended holiday visit, she had ample opportunity to observe her sister. While Melody still possessed the natural grace she always had, the bloom upon her cheeks seemed dimmed. Jane suspected that the unseasonable March snows, which kept so many families indoors, had limited the opportunities for the society that her sister so delighted in. If could she leave the house to take walks, perhaps that might have restored her humour but in want of occupation, Melody had become afflicted with severe melancholy.

Jane knew all too well how the want of purpose could oppress even the brightest spirit.

And so Jane had taken it upon herself to host a card party, inviting all those neighbours who were willing to make the trip to Long Parkmead.

She expected this would delight Melody, but was surprised to find, upon glancing up from a game of whist, that her sister stood by the window, looking out at the snow. Her golden curls seemed to cry for sunlight quite as much as the daffodils, which peeked above the layer of snow outside.

Jane reached the end of her game and waited while she and her partner, her mother’s friend, Mrs. Marchand, counted their tricks. Mrs. Marchand was only too delighted to discover that they had nearly twice as many points as their rivals. Leaving her to triumph in their victory, Jane excused herself from the table upon the pretext of wishing to cool her temples by the window and went to her sister.

“Have you had much luck this evening?”

“Hm? Oh . . . some.” Melody pulled her shawl up around her shoulders. “I won a round of lottery.”

She seemed disinclined to say more, where once she would have soliloquised about how many fish tokens she had won at the card game.

“And you are satisfied with that?”

Melody shrugged. “My head aches.”

Knowing that the headache was a fancy of her sister’s to explain away her lowness, Jane sighed. Her breath frosted the window for a moment. Struck by an idea, she leaned forward and blew on the glass. She drew a bird on the fogged pane. “Do you remember when we tried to draw snowflakes in all the windows for Christmas?”

Melody shook her head, a single line appearing between her brows. Forcing a smile, Jane tried not to let the disappointment show on her face. It had been one of the treasured memories of her childhood. “I suppose it is not surprising. I was thirteen, so you could have been no older than three, I think. You wanted to learn glamour but were too young to hold the folds. I showed you how to fog the glass and you went around ornamenting all the windows.”

“Little has changed then, since I still cannot work glamour.” Melody glanced over her shoulder. “How is Vincent enduring the party?”

“Tolerably, though I had to rescue him from Mrs. Marchand once, who tried to insist on his being the fourth for a hand of whist.” Jane wrinkled her nose at the thought of her taciturn husband being forced to sit next to their sociable neighbour. He now stood engaged in conversation with her father. Though he held her father in high esteem, Vincent still had an edge of tension to his stance, simply from being in a room with so many people.

“La! He is patience embodied.”

“I promised him that as soon as we perform the tableau vivant Mama requested, he can retreat under the pretence of fatigue.” An illusion such as a tableau vivant would not ordinarily be enough to tax the strength of a professional glamourist such as Vincent, but Jane was quite willing to take advantage of her mother’s sometimes excessive imagination to offer her husband an escape.

“I declare, I do not know how you managed to attach such a hermit, but sometimes I am exceedingly jealous.” The shadow came back to Melody’s countenance as she leaned forward to blow on the window. With a finger, she drew a simple snowflake. “I almost remember, I think.”

“I look forward to wishing you joy.”

“You may hold that wish for a long time.”

“With your beauty? My dear sister, you were made to attach gentlemen.” Jane tried to tease her sister back into something like her natural spirits.

“Really?” Melody dropped her finger and turned to face Jane fully. “Who should I attach?” She glanced toward the room filled with their friends and neighbours.

Standing with her sister made the room change in aspect, as though a glamour had been drawn over it. Where before Jane had noted the merriment and general air of pleasant conversation, she now attended to the individuals. The room seemed composed almost entirely of women, young and old. There were men, to be certain: Mr. Prater, the old vicar; their father, Mr. Ellsworth; Mr. Marchand and his assembly of daughters . . . but there was not a single young bachelor. Once their neighbourhood had held several eligible gentlemen, but many of them had gone away to fight Napoleon and never returned. Others had left for different reasons.

Jane had thought that Melody’s depression was due to being confined indoors, but her loneliness was of a far deeper nature than that.

The morning after the card party, Jane made her way down the hall to her father’s comfortable study at the back of the house. He had always been a source of steady counsel for her, and she had hopes that he might have some thoughts on what to do for Melody.

Voices met her in the hall. She hesitated on the threshold of the study.

Mr. Ellsworth looked up from a sheet of paper that he was bent over with Mr. Maulsby, the estate manager for Long Parkmead. “Come in, Jane. We will be but a moment longer.”

She slipped into the leather wingback chair by the fire and made herself comfortable. She had known Mr. Maulsby all her life and he had long been a good steward for her father’s estate. His father, before him, had attended to the running of the fields and harvests and all the other things, which good English culture required. He was a tall man with a perpetual stoop to his shoulders, which Jane thought must come from spending so much time hunched over his papers or looking at the ground. His hair had silvered in time, like her father’s, but remained as thick on his head as always. He nodded to her as she settled in her chair, but did not break his conference with his employer.

“I’ll tell you true, Mr. Ellsworth, I think we have to replant the south and east fields. The sprouts were just coming up when this hit and now they’re black in the ground.” The manager tapped the paper with one nail-bitten finger. “Perhaps the northwest one too, but that gets more sun because of the elevation, so it might be all right if the snow passes soon.”

“You are certain? No—no, I know that you are, or you would not come to me.” Mr. Ellsworth sighed heavily and scratched his thinning pate. “Well. Well. You had best order the seed, then, before the prices go up any further.”

“Yes, sir. That I’ll do.” Mr. Maulsby rolled up the paper. “It’s worse up north, I hear. The ground’s not thawing at all. If this keeps up, we’ll see food riots.”

“Let us hope, then, that the weather warms soon.”

“Aye, or we’ll have troubles in the autumn bringing in the harvest.”

“We shall fret about that when it happens.” Mr. Ellsworth clapped the estate manager on the shoulder and saw him out. After the man had gone, her father stood in the door for a moment before sighing heavily. When he turned back to Jane, he had a smile on his face, which she was certain he wore solely for her benefit. “What can I do for you, my dear?”

“I feel that I should ask the same of you.”

Mr. Ellsworth grimaced. He glanced down the hall and shut the door. “You will not tell your mother?”

She shook her head. Mrs. Ellsworth was a good woman and not without understanding, but her worries sometimes carried her far beyond reason. Jane was well used to guarding her mother from things that would upset her without need.

Settling into the chair opposite her, Mr. Ellsworth crossed his legs and stared into the fire. He was silent for some minutes, fingers moving across the arm of the chair as though he were plotting on the leather what to tell her. “Well. Well . . . as you might have heard, the cold has killed our barley shoots. We can replant, but it is an expense I had not looked for.” He offered her a sorrowful smile. “It will not ruin us. Others will not be so lucky. But there is still a cost, and I worry, as always, about making sure that my daughters are provided for.”

Jane reached over and took his hand. “You know that I am provided for, at least.”

He chuckled. “I am your father. One never ceases to worry.” He patted her hand. “But—but you are correct. Melody is my chief concern. I will not need to touch her portion, or anything so severe, but in spite of my steward’s brave words, I must plan as though this harvest might fail.”

“Do you think that likely?”

“No. But then, I have never seen it snow so late in the year. A flurry, perhaps, but we are very nearly in April and there are eight inches of snow upon the ground. I would be a fool not to consider how we might retrench if the harvest were to fail.” He shook his head and patted her hand again. “Do not let your mother hear the word ‘retrench.’ ”

Jane could well imagine the terrors her mother would create at any talk of practising economy. “I promise I shall not.”

He released her hand to tend the fire. “I had hoped to send Melody to London for the Season. She is . . .”

“Depressed.”

“Yes.” Jane had the uncomfortable sense that her father was waiting for her to offer a cure for her sister’s depression. She had none. “Perhaps Bath? It is not so expensive, and might offer her some prospects.”

“Do you think? The last trip went so poorly that I fear a trip to Bath might revive her wounded sensibilities.”

Jane bit the inside of her lip. She had not considered that at all. The road to Bath was where Melody had lost all hope for the man she had loved. “We are both resolved, though, that a change of scene would do her good?”

“Indeed.” Mr. Ellsworth shifted his chair closer to the fire. “But perhaps we are showing unnecessary alarm, and London will be possible after all.”

Outside the window, the snow continued to fall. Jane could not allow herself to hope that her father’s optimism was correct.

Two

Weaving Invitations

Jane entered the parlour carrying the morning mail, eager to show her husband the letter that they had received from London. She stopped in surprise in the doorway. The snow had ceased during the night, and the morning sun made a dazzling wave across the parlour. It cast Vincent’s form into severe relief as he stood next to the fireplace, scratching his back against the corner of the mantelpiece. His eyes were closed and his brow furrowed in concentration. In spite of his blue coat of superfine wool, tan trousers, and tall boots, Vincent looked like nothing so much as a bear come in for the winter. Jane half expected him to produce a honeycomb and begin eating it. She laughed, covering her mouth in delight at the image.

Vincent opened his eyes in alarm, springing away from the mantelpiece. He blushed charmingly. In an instant, his aspect changed from that of a bear to that of a schoolboy caught out. “My back itches.”

“So I see.” Jane crossed the room and set the letters on the side table. “If you remove your coat, I can scratch it for you.”

She helped Vincent shrug out of his coat, admiring once again her husband’s fine form. How had a woman as plain as she attached such a figure of a man? She did not understand it, but any doubt she might have held of her husband’s deep love for her had long since vanished. It was the source of her greatest happiness.

Jane curled her fingers and applied them to Vincent’s back. Even through his waistcoat, she could feel the knots and ridges of scars where he had been flogged by Napoleon’s men. They had healed without infection, thank heavens, but the cold weather often caused the new skin to itch.

He heaved a sigh of relief, leaning into her hand. “Thank you, Muse.”

“Shall I fetch some liniment from mother?” Jane managed to keep the smile out of her voice and offer the question with sincerity.

“No!” Vincent straightened, shuddering. “I mean, thank you, but—” He turned to regard her and broke off as he saw the smile she had been unable to keep from her countenance. “Muse. You are wicked at times.”

“Me? I thought you were the one who was not a nice boy.”

“But I am a nice man, whereas you are cruel and heartless.”

Vincent rubbed his hair, mashing it against his head. “Can you imagine what your mother would do if I were to actually admit of an infirmity? Even one so small as dry skin?”

Laughing, Jane wrapped her arms around her husband and pulled him close. Her mother was peculiarly good in a real crisis, but in the absence of difficulties, tended to create them. A sliver could promote thoughts of gangrene. “I promise that I will protect you from her remedies. When I go to town next, I shall pick up some liniment, though. Until then . . . turn around and let me continue.”

He complied, letting his head hang forward with a grunt of contentment. Her bear had a sweetness beneath his grumbling exterior. “You are very good to me. Even if you are wicked.”

“Hush.” Jane slipped her hand around his chest to brace him as she dug her fingernails into his back. He relaxed into her embrace, the warmth of his chest serving as a balm against the chill. Outside, the snow sparkled in the sunlight. With luck it would begin to melt soon, though that would leave the roads dirty and unpleasant for a while yet. “Oh. I nearly forgot why I came in. We had a letter in the morning mail.”

“Is it Major Curry? I am wanting his answer to more than a few questions about percussion glamours.” The military glamourist had been assigned to tend to them while they recovered from the Battle of Quatre Bras, and had become a great friend due to his kind and attentive care. Afterwards, Vincent continued to trade letters with him, comparing techniques that could be shared between ornamental and military glamours.

“It is a request to commission us.”

Vincent’s head rose with curiosity. “Anything of interest?”

After they had created the glamural for the Prince Regent’s New Year’s fête for the second year running, the Vincents had received scores of commission requests, but most had been from parties who could not afford them, or who lived in parts of the country they had no wish to visit, or were simply banal. Now, though, Jane was restless and wanted to be doing something. “I think so. It is from the Baron of Stratton—sent by Sir Lumley—which gives me hope that he has some taste. It is on the table if you want to read it yourself.”

Vincent lifted Jane’s hand from his chest and kissed it, before pulling away to fetch the letter. He carried it to the window for better light and stood reading it, a shade against the snow. “He offers excellent terms. I suspect Skiffy informed them.”

Jane still could not bring herself to call Sir Lumley St. George Skeffington by his college appellation, but then he and Vincent had known each other through their connections at Eton so could be allowed that familiarity. “Do you think he is trying to draw you to London?”

“Doubtless.” Vincent pointed to a line near the top of the paper. “I must say that their notion of hiding a musicians’ gallery behind a glamural of songbirds is appealing. I wonder . . . we might scatter birds throughout the room to carry out the theme.”

“Perhaps we could experiment with a variation on the lointaine vision to transfer the sound to other parts of the room so that the music comes from the various birds.”

Vincent canted his head to the side and stared into the middle distance with a look that Jane recognised, and she knew they were going to London. Vincent had already begun drawing plans in his head. Jane, too, had plans that she had begun sketching, but they did not involve glamurals—or, at least, not directly. Her plan involved her sister.

“Vincent . . . do you think we might take Melody with us?”

He straightened his head and regarded her. “Would she enjoy it?”

“I think the change of scenery can only do her good, and her marriage prospects would be brighter with London’s social season.”

“I suppose. But would she not prefer a husband who could keep her close to your family?”

“Who?” Jane waited for Vincent to see that there was no one in their neighbourhood with eligible sons.

He nodded slowly. “Then, by all means, she should come.”

“Thank you, my love.” Jane traced a hand along his arm. “Would you issue the invitation?”

Under Vincent’s sleeve, the muscles of his arm tightened. “Me? Would she not rather have it from her sister?”

“It would be natural coming from me, but I think it would mean more if it came from you.”

A minute whine of protest escaped him, as though he had imperfectly held his breath. He was, to the best of her knowledge, unaware that he made this sound when afflicted with contrariety. Jane had not enlightened him, as it proved useful to know with what he struggled. She waited as he thought, watching until the lines between his brow smoothed. He nodded. “Of course. Though I shake at the thought of your mother’s answer to our departure.”

“Particularly for a glamural.” Taking pity on her husband, Jane said, “Well, I will relate that much, at least.”

“Thank you, Muse.”

With that settled, she helped him back into his coat and led him down the hall to the breakfast room, where the rest of the family still sat at table.

Mrs. Ellsworth had a volume of correspondence before her from acquaintances likewise afflicted with nerves. Mr. Ellsworth kept his newspaper up as a shield, making the occasional noise in answer to his wife’s exclamations.

Melody had his discarded pages. As Jane and Vincent entered, she clipped an item from the paper—likely a description of London fashion. She alone glanced up. “You look as though you have news.”

Mr. Ellsworth folded his paper with interest. “I suspect so, the way you hurried out with that letter.”

Smiling at her father’s discernment, Jane nodded. “Indeed. We have received a commission from the Baron of Stratton for his London house.”

“London?” Her father raised his brow. His gaze darted toward Melody, demonstrating a wish that she might accompany them.

Before Jane could reply, Mrs. Ellsworth exclaimed. “Oh! Oh, I do hope that you will decline it. I hardly see how it is possible, with your troubles. Sir David, say that you will not accept.”

Vincent shrank at the sound of his title. He had been simply Mr. Vincent when they met, and seemed more comfortable that way, but her husband had become Sir David Vincent when he was raised to the honour of knighthood last year. He felt it was ostentatious and would have avoided the title altogether if he could, but one did not say “no” to the Prince Regent. Jane had attempted to explain his preference to her mother, but he would always be Sir David to her.

Jane stepped in to save her husband. “Mama, you must see that we have already been performing glamours.”

“But you should not try your strength so soon after your troubles. Indeed you should not. Why, last night, you were exhausted after a tableau vivant. What might a glamural do?” Mrs. Ellsworth shook her head, the lace of her cap fluttering. “I am shocked that you would attempt to work glamour at all. Who knows what could happen? Why, the house might explode!”

Vincent coughed and covered his mouth. Though she was used to her mother’s hysterics, even Jane found it difficult to not laugh outright at this notion. “That is hardly possible, as glamour is largely ornamental. If it could make something explode, then that technique would be used in the military.”

“But it does! What of Major Curry? And I do not see why, if coldmongers can make things cold, you could not make something explode.”

“Coldmongers may only chill things a few degrees, and it is an—” Jane stopped herself from saying ’unstable,’ which her mother would misconstrue. “—a purely temporary effect.”

“No, no! They are what is making the weather so unseasonably cold. I have a letter here from Lady Worrick who explains it all. She got it from a lecture in London by a Professor Van Reed. If that is the case, then I see no reason that glamour could not explode.”

“I am afraid the lady misunderstood what she heard. The thermal transference alone—” Jane broke off again, recognising the impossibility of Mrs. Ellsworth comprehending the full scientific reasons that her fears were unfounded. The notion that coldmongers could affect the weather was so far from truth as to be ridiculous, and glamour causing explosions was even more so. While it waspossible to warm things with glamour, the effort was so great as to be impracticable. Moreover, that form of glamour took an unhealthy toll on its practitioners, and resulted more often than not in death. No one used heat glamours for that very reason. But knowing her mother, invoking the mere hint of death would only serve to heighten her fears. “You may trust me that coldmongers cannot affect the weather.”

Melody slid the paper she had cut out closer to Jane. “I read something of that! Here it is: ‘Though it is too much to state that the Worshipful Company of Coldmongers is the cause of the current weather, many educated gentlemen of our city have raised the question of whether they might be, at least unintentionally, the cause of the alteration in our climate.” She squinted at the page. “Oh, but wait . . . the writer goes on to say that it is not possible.”

“There. You see, Mama?”

“What can a writer know?” Unrelieved, Mrs. Ellsworth sank back in her chair. “Oh! It is too much. And in your state!”

“My state is one of general health.” Jane glanced at Vincent, who shifted anxiously, as if he were about to quit the room. She had no wish to revisit the subject of her miscarriage. Vincent still felt it was his fault, when he had been as much a victim as she. Though it had happened eight months previous, it seemed as though her mother would fix on nothing else whenever Jane or Vincent picked up a thread of glamour. As they were professional glamourists, this presented a few challenges. “Truly, I have been quite well for some time now.”

“But you are so pale. I cannot believe that you are in good health if you are so pale, especially with such an unhealthy flush to your cheeks.”

Melody laughed and set her paper down. “La! She cannot be both pale and flushed.”

“But of course she can! Look at her, poor dear. I fear Jane’s health will never be the same if she continues on in this manner.”

Jane said firmly, “There will be no difficulty in going at once, as we are both quite well. Indeed, Mama, to decline a connection such as this would be to our detriment. Being in London during the Season has every advantage.”

Vincent cleared his throat. “In fact, with the Season approaching, we were hoping that Miss Ellsworth might accompany us.”

“Oh.” Melody’s blue eyes widened with astonishment. “Oh!”

“Unless you do not wish to, of course.” Vincent offered her abow.

“Not wish to? I should adore going to London above all else.” The anticipation already restored some of the bloom to her features.

The prospect of London appeared to affect the sensibility of more than one person in the room. Mrs. Ellsworth clapped her hands together and bounced in her chair like a girl a quarter of her age. “Oh! London in the Season! We shall have such a merry time.”

Beside Jane, Vincent emitted his trifling whine, audible only to her ears. Jane raised her hand to stop her mother’s effusions. “We had thought only to take Melody with us. You would not wish to leave Papa all alone, and he can hardly leave, with all the work to be done around the estate.”

“It is true, my dear. I would be intolerably lonely if you were to go as well.” Mr. Ellsworth caught his wife’s hand. “It has been too long since we had the house to ourselves.”

“But she must have a chaperon! How can Melody go if I do not accompany her and protect her from improprieties?”

Jane smiled, more than ready with an answer for that objection. “That is no trouble at all. As I am a married woman now, I am more than able to act as Melody’s chaperon.”

She had the satisfaction of seeing her mother unable to protest. More to the point, Vincent stopped holding his breath.

It was nearly another month before they were able to make the move to London. There were terms to negotiate with the Baron, a house to rent, trunks to ship, and finally their own travel arrangements to make. Though the snow had abated, the roads remained clogged with mud and would be slow going for a hired carriage. Even as the calendar had turned to April, the weather remained tenaciously chill. Snow still capped the hills as though it were January. It was a great relief when they clattered onto the London pavement and saw the great buildings crowd around them. Everywhere they looked, people thronged the streets, wrapped up against the cold.

Glass-front shops lined the roads and displayed their merchandise to tempt passers-by inside. The more garish establishments had façades smothered in glamour to draw shoppers’ attention. Grocers set out winter greens and squashes under awnings that dripped on the unguarded. Carriages, hacks, and swells on horseback crowded the streets. Melody pressed her face against the glass and exclaimed at it all.

Jane leaned against Vincent with some satisfaction that the novelty had already begun to revive Melody’s spirits. She had been to London before, but there is a distinction between coming as a child with one’s parents, and arriving as a young lady who was Out for the Season. A very great distinction indeed. Jane’s father had given her some banknotes before they left with instructions that she was to buy Melody some new dresses and any other fripperies she desired. This was a task that Jane would undertake with pleasure.

Their carriage slowed. Outside, Jane could hear a clamour of voices. After a moment, the driver turned the horses and drove them onto a side street. Through the window, she glimpsed the road they had been on. A mob of people clogged it, shouting and dragging a large wooden frame out of a building. A man raised a sledgehammer over his head and dashed it into the side of the frame.

“What is happening?” Melody changed sides of the carriage and gave the street her attention.

“From the looms, I would guess they are Luddites.” Vincent lowered the window and the unintelligible rumble became a roar. He leaned out to address the driver, but his words were lost among the voices of the crowd. After a moment, he pulled his head back in and fastened the window. “Just so. He has another route that will take us around the disturbance.”

When they had been in London last, working on His Royal Highness’s commission, Jane could not recall this sort of disorder in the city, though she would grant that they had been busy the entire time. “Is this common?”

“Not in the City. I have read of disturbances in the North, but did not know that they had been felt in London.”

Jane cocked her head. “What are Luddites?”

“The followers of a imaginary man.” Melody leaned closer to the window. “They claim to follow Ned Ludd, but there is no evidence that there is such a man. They are largely weavers who have lost their place to the new weaving machines, but others who oppose progress support them.”

Jane could not help but be astonished. “How do you know that?”

“La! It was in the papers.”

As the carriage went over a bump, Jane swayed against Vincent’s side. “Those were looms, then?”

He nodded. “I cannot be entirely unfeeling toward their complaint, but at the same time, we do live in the modern age.”

“I do not care for modern times, then.” Melody settled back in her seat with a decided flounce. “If they make people act like madmen.”

“More than mere modernity can induce madness.” Vincent glanced out the window as the carriage turned on to a smoother street. “Ah . . . this is ours. Look—”

Anything further he might have said was lost as Jane and Melody crowded to the windows to look out. The carriage filled with cries of, “That shall be our baker!” and “What cunning hats!” and “Is that a bookseller?”

“That is not just a bookseller; that is our home.” As the carriage pulled up in front of a handsome red brick building, Vincent opened the door and stepped out.

The façade was striking, with a total of five bays, three that projected slightly toward the street while the two end bays jutted forth almost like towers framing the building. The whole structure rose four stories above the foundation, with a multitude of narrow windows. The house had been divided into three addresses at some point, with the one in the centre being taken up by Beatts and Co., Booksellers, and the one to the right being occupied by McGean’s Cloth, Laces, and Ribbons. They were to occupy No. 80, on the left.

Jane and Melody followed Vincent out of the carriage as a footman came out to help the driver with the trunks they had brought with them from Long Parkmead. The housekeeper who came with the establishment met them at the door.

Mrs. Brackett was an older woman with iron-grey hair pinned up severely.

“Welcome, Sir David, Lady Vincent.” Her gaze landed on Melody and she gave an approving nod, as though glad to have a young lady under her care. “And Miss Ellsworth. It is a pleasure to welcome you to Schomberg House.”

Mrs. Brackett led them through the front door into a wide marble hall. Even divided as the house was, it still opened on to parlours to either side and had a stair going up farther. The small staff that had come with their terms for taking Schomberg House gathered in the foyer, at attention. With the house, they had acquired a cook, two housemaids, and the added luxury of a footman who could double as a valet.

It was a smaller staff than they had at Long Parkmead, but more than Jane had managed when they last lived in London. Then, they had been so consumed by work that they had one small apartment and only kept a maid-of–all-work. Here, though, Jane planned to entertain when they were not working, in the hopes of finding a suitable match for Melody.

Her sister was alight with wonder, sighing over all the accoutrements of the foyer as though she had never been indoors before. In truth, the furniture the house came with was clean but a little shabby, as though the previous occupant had used it harshly in spite of Mrs. Brackett’s efforts. Still, the side tables had arrangements of evergreens in the absence of flowers, and the paintings on the walls were of very good quality.

“Thank you, Mrs. Brackett. Would you see that our trunks are settled?” Vincent pulled off his greatcoat and handed it to one of the maids.

“Certainly, Sir David.” Mrs. Brackett nodded to the staff, dispersing them back to work. “Shall I show you to your rooms?”

“If you would do that kindness for Miss Ellsworth.”

The sound of her name called Melody out of her raptures over a folding screen in the corner. “But what are you going to do?”

“I want to show Ja—” He paused and corrected his address in front of the staff. “I have something to show Lady Vincent. You do not mind?”

Jane supposed that she would have to become used to calling him Sir David as well. If they were to use their position to make a good connection for Melody, then they could not continue to act as simple artisans. The staff would talk, and that news would circulate through society as gossip, even if no one admitted to gossiping with their valet or maid.

Melody shook her head and turned in place. “I shall have quite enough to do with settling in. Oh, what a delight!”

With a short bow of thanks, Vincent motioned Jane to the next flight of stairs. She paused only long enough to make certain that Melody truly was comfortable before following him up to the first story and again to the second. They went up again to the third floor. Vincent paused outside a wide door. “I hope you like this.”

Jane raised her brow in question.

In answer, he threw the door open. The whole of the top story was taken up with a wide room bright with skylights and surrounded by windows. The effect made it seem open and airy, as though they were outside. The broad wood beams of the floor were stained here and there with paint, but it did nothing to mar the sense of wonder that the room provoked.

“What . . . how? What is this? Vincent, why did you not tell me?”

He laughed and spun her around in a circle. “When I was a pupil at the Royal Academy, a picture dealer had his establishment here. I visited many times.”

“You told me as much when we saw it on the list of properties to let. But the studio?”

“I wanted to surprise you. And look.” He led her over to a corner, where a tube projected up out of the floor. Atop it was a bell, with a string that ran down into the tube. “Do you know what this is?”

Jane had only seen engravings, and never been in a house that still had a boucle torsadée installed. “A speaking tube? Truly?” In the 1740s, these had been all the rage in wealthy homes and allowed near instant communication within the household through the use of glamour. A long thread of glamour ran through the tube and could be set to spin, carrying sound from one point to another. Since the sound ran continually, a glamourist would have been stationed in an operator’s booth in the servant’s quarters to start and stop the boucle torsadée. Bells like this one signalled the glamourist. They had gradually fallen out of favour as the fashionable set realised that it was just as easy for the servants to eavesdrop as for them to send orders to the kitchen. Between that and the maintenance the glamour required to continue working, people had returned to using servants. The only vestige that remained in most of those homes were a system of bell pulls. Jane bent over the tube to peer down it. It had been filled in at some point, no doubt to prevent drafts. “Did it still work in your college days?”

He shook his head. “The glamour frayed long before the picture dealer took over the house. We toyed with trying to get it to work again, but most of the tubes were blocked, and the boucle torsadée requires a clear line of sight to function. The operator’s station is a linen closet now, but this artefact . . . . It makes me think of what glamour could do, if we could but think of new methods to try.” He slipped behind her and wrapped his arms around her waist. “Do you see the possibilities here, Muse? A place to practice our art uninterrupted. We might continue to explore glamour in glass.”

“Without fear of explosions?”

He chuckled and spun her in his arms. “Well . . . perhaps none of glamour.” Vincent reached back with his foot and kicked the door shut.

Without a Summer © Mary Robinette Kowal 2013