Skin of the Wolf by Sam Cabot

Skin of the Wolf by Sam Cabot

#2 A Novel of Secrets

Publication Date: Aug 4th

Add it to your Goodreads shelf / Amazon wishlist

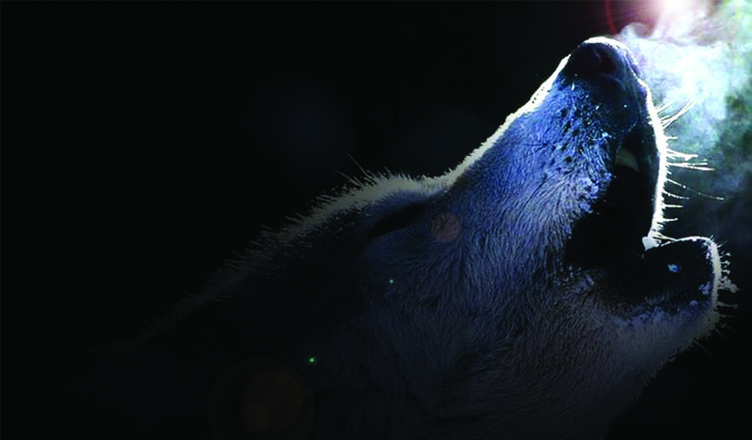

Months after Father Thomas Kelly, art historian Livia Pietro, and scholar Spencer George found themselves racing through Rome in a desperate effort to locate and preserve an incalculably valuable docu-ment, the three are about to be reunited in New York City. Thomas, still trying to assimilate what he learned—that vam¬pires exist, and that Livia and Spencer are among them—is looking forward to seeing Livia again. Livia is excited to be allowed into the back room of Sotheby’s for an exclusive viewing of an ancient Iroquois mask. And Spencer’s in love. But before the three can meet, Spencer is badly injured when he’s inexplicably attacked in Central Park—by a wolf.

That same night, a Sotheby’s employee is found brutally murdered. Steps from her body is the mysterious native mask, undamaged amid the wreckage of a strug¬gle. As rumors begin to swirl around the sacred object, Thomas, Livia, and Spencer are plunged deep into a world where money, Native American lore, and the history of the Catholic Church collide. They uncover an alarming secret: The wolf is a shapeshifter, and the mask contains a power that, if misused, could destroy millions of lives with the next full moon.

In Skin of the Wolf, Sam Cabot masterfully blends historical fact, backroom conspiracy, and all-encompassing alternate reality as the Noantri discover they aren’t the only humans set apart by their natures—there are Others.

EXCERPT

***This excerpt is from an advance uncorrected proof***

Copyright © 2014 Carlos Dews and S.J. Rozan

—1 –

Brittany Williams slid the box with the Ohtahyohnee mask into its place on the shelf. The holding room was almost empty; most of the items for the upcoming auctions were already on display. Not quite all: as usual, Native Art had only been given three galleries. Not like Old Masters, which always got a full floor when their big show came up. Or Asian Art, actually three separate departments with three Specialists, eight assistants, and two entire floors for two whole weeks in the spring. No, Native Art didn’t even have enough space to exhibit all their pieces and Brittany and Estelle were expected to do everything themselves.

Estelle was a genius, though. The pieces not on display were the ones buyers would be least likely to be familiar with, pieces they might have to be talked through to understand. Making people have to ask to see them was a way to ensure that either Estelle or Brittany would be right there to explain and extoll. Brittany had gotten a French doctor interested in a Spokane doll yesterday and she’d made sure Estelle knew it. If he bought it Brittany wouldn’t get a commission—God forbid Sotheby’s should work like that, as though any of this were about anything besides money—but Estelle would remember. Even in the backwater that native art had turned out to be, it was all about people knowing how good you were. And this Ohtahyohnee: according to Estelle the owner insisted it not be shown until the last possible minute, which by Sotheby’s policy was the day before the auction. This was the star item for Friday, slated to go on display tomorrow morning. Brittany didn’t believe for a minute an owner would hold a piece back that way, especially one causing a big stir. The first Eastern tribe wolf mask to be auctioned in, like, ever? As much as they liked making money, owners liked to show off. There was a lot of nyaah, nyaah in the collecting world and this was an absolutely primo opportunity for it. But holding it back was pure Estelle. The only way to create more demand than its existence did was to tell people you had it and then not let anyone near it.

Okay, Estelle might be a genius, but she abused her assistant just like every other Specialist. She was out to dinner kissing some German museum director’s ass and Brittany would be here late into the night yet again, getting ready for tomorrow.

She went into the inner office and sat at the computer to key in Estelle’s scrawled notes of the people who’d come to see pieces today. After that she’d be last-minuting all the oh-so-fascinating pre-auction details: making sure there were enough black velvet cloths of all the right sizes for the sale pedestals, dusting and polishing each piece one final time. Things no one with an art history degree, and God knows no one with a trust fund, should have to do.

B-o-o-o-oring. She yawned. She’d perk right up with a little coke and a night of clubbing, but no way that would happen. Unless she quit. Which she’d thought about. She didn’t want to wake up one morning and find she was like Estelle and her friends from this afternoon. Dried-up old prunes, not even cougars, just three single, sexless, middle-aged women. Well, that Italian one, there was something about her. She could have been hot, but she didn’t do anything to help herself and God, what was she, like, fifty?

Brittany didn’t want to give Daddy the satisfaction of quitting, though. He hadn’t minded that she’d majored in art history, but he’d been incredulous when she’d actually taken a job. It wouldn’t last, he sneered to Mom. Some Switzerland ski trip or Caribbean beach would beckon and she’d follow like the airhead she’d always been. She wasn’t cut out for working.

So she stayed, because screw him. But maybe she really should reconsider the native thing. The art was okay, but with Old Masters or Contemporary or even American Outsider, you had a whole gallery scene in addition to the museums and auction houses. You didn’t have to be a Slave of Sotheby’s, the assistants’ name for themselves. Which all the Specialists knew, and didn’t care. Sure, there were native art galleries, but not in New York. They were in the Southwest or in places like Seattle, and no way she was going there. It wasn’t like she loved this art particularly, not like Estelle did. And Katherine Cochran, she was even weirder. Brittany suspected they actually bought into it, thought some of the pieces were alive and had powers. Brittany always took care to look thoughtful when they talked like that, but seriously? No, she had to get out of here. No one ever said a Koons had superpowers. Not all that many people even said they were any good. Brittany had only gotten into native art in the first place because of that Chippewa guy, Stan, from junior year. God, he was hot, and she’d really gotten to Daddy with that one. He’d have been happier if she’d hooked up with a Jew or an Irish potato farmer.

She looked up when she heard the outer door click open. The Jamaican guard, Harold, this was his night. She’d taken a run at him but he didn’t want to lose his job. Maybe she should try harder. He was big, with broad shoulders, and talk about pissing off Daddy! And he was early tonight, so maybe he wasn’t as immune to her as he pretended. She swept her golden hair off her forehead—at $300 every few weeks, it better be golden—so it would fall back into place when she looked up. Harold would pass through the storeroom and then, seeing her light on, stick his head in here. She recrossed her legs to reveal a little more thigh.

He didn’t show up, though. She didn’t hear the outer door shut again, so he must still be in the storeroom. What was taking him so long? He couldn’t be, like, afraid of her, that she’d make another pass? She smiled. Or maybe he was trying to figure out a line to use, because he’d decided to do her but he wanted her to understand it was his idea. As if. She stood, tugged the neckline of her sweater a little lower, and went into the storeroom.

Nothing to be seen. “Harold?” A sense, then, that someone had just frozen, that movement had stopped. God, what a coward he was. She stepped up the aisle in her red-soled Louboutins, shoes that turned men to jelly even on women not as beautiful as she. She made a right and halted. Wait. What? She didn’t get what she was seeing, couldn’t grasp this. The Ohtahyohnee’s box was open; the mask grimaced up at her. Standing over it, staring down, quivering in taut-muscled rage, was a huge gray dog. How the hell did that get in here? Brittany started to tiptoe backwards. Her stiletto heel caught the rug and she stumbled against a shelf. Just a tiny clunk, but the dog whipped its giant head in her direction. Its eyes glowed and its lips peeled back in a hungry, insane smile. Brittany took two more slow steps back while the dog just stood. Then it crouched to spring.

Brittany spun and dashed for the office, but the Louboutins weren’t made for running and she tripped. She tried to scramble up from her knees but the dog crashed into her, knocked her down. Its breath stank, it weighed a ton. She struggled but the mouth slavered and the teeth gleamed and for the first—and last—time in her life, Brittany was prey.

—2 –

“In a general sort of way,” Spencer George announced, burrowing more deeply into his coat, “I do not enjoy this weather. In case you wondered.” His eyes watered as yet another blast of cold air hit them.

Bare-headed and gloveless, the larger, younger man beside him laughed. “Why not? It’s beautiful! Look at that moon—full tomorrow! Look how bright the stars are! When do you see that in the city? And listen to that wind! Come on, it’s a gorgeous night.”

“Michael, I am fully prepared to accept that for your people, priding yourselves as you do on your oneness with the natural world, it’s conceivable shrieking wind and glowing stars are sufficient to neutralize the discomfort of numb toes and frostbitten ears. I would further stipulate that I myself am a decadent white man who long ago lost touch with Mother Earth.” Longer ago than you can imagine, he added sourly to himself, and I can’t say I’ve missed her caress. “I acceded to this absurd notion of a walk through Central Park purely out of my high regard for you and respect for your wishes. Also my fear that you’d change your mind about joining my friends and myself for a drink if I didn’t.”

“You weren’t afraid of that.” Michael grinned.

“That’s true. It sounds good, though, doesn’t it? It makes me appear unselfish and noble. Willing to suffer for those I cherish.”

“Only if I believed it.”

Spencer sighed. “Then what am I doing out here? Really, Michael, if this is your idea of a good time, we might be less compatible than I hoped. Talking of ‘hoped,’ did you see your mask, by the way? Was it as exceptional as you’d anticipated?”

Michael didn’t speak immediately. With a small smile, he said, “It’s beautiful.”

“Hmm. Beautiful. I detect a note of disappointment, however. Are you—” He stopped as Michael grabbed hold of his arm. “What?”

“Shh.” Michael stood still. His eyes narrowed and his nostrils flared. He turned his head slowly left, then right, and loosened his grip. “Go,” he said.

“What are you—”

“Leave. Go home. I’ll come soon.”

Spencer didn’t move and didn’t answer. His own Noantri hearing, acute as it was, detected no sound beyond the howling wind and the hiss of the city’s unceasing traffic. Nor did he scent anything unusual riding the rushing air. But he felt something: a current on his skin, a dark voltage new to him but charged, unmistakably, with danger.

A roar blasted the night. A blur of movement: Spencer spun, but not in time. Something smashed into him, knocked him painfully to the ground. Something alive, he knew, because, while he lay on his back, breath knocked out, he saw it bound up and after Michael, who was racing away into the darkness under the trees.

—3 –

Michael Bonnard took off along the darkest route he could find. He sprinted up and over a small hill, loped down the far slope in great long strides. Icy wind whistled around him. He had to lead Edward away from Spencer.

This was Edward, no doubt. It astounded Michael to find him in the city—Edward hated the concrete streets, the crowds, the cars, the steel—but he was here and he was raging. On the bitter air Michael could smell Edward’s scent, sense his heat, feel his fury. A fury so great, an anger so overpowering, that Edward had Shifted.

Disaster. For Edward it was always, always anger that triggered the Shift. Michael could use anger, but other states also: panic once, as a child; another time, the exhilaration of first love. It was harder for him, though, no matter what. His flashpoint was higher. For Michael the Shift had to be intentioned, a matter of determined will.

Plunging into a tangle of shrubs, he tore at his clothes, trying to free himself, trying at the same time to summon that overwhelming, cresting sensation that would be his own trigger. Anger. Fear. Shock. Whatever he could use. Michael didn’t know why Edward had come here, what powerful need had driven him so far from home to a place he detested: but right now, Michael knew with certainty, Edward was burning for a kill and he was hunting.

– 4 –

Spencer gathered himself, drew a deep breath, used it to mutter an oath, and raced after Michael.

At the time of his Change, Spencer George had been a landed aristocrat with an estate in Sussex. He could ride a horse, wield a sword, shoot accurately with a flintlock pistol, and creditably execute every dance in Ebreo da Pesaro’s De Practica. Once he’d become Noantri, his grace, strength, and stamina all increased. He was grateful for, and delighted in, that fact in the bedroom; but outside that sanctum, with the exceptions of shooting, swordplay, riding, and dancing, physical exertion had for five hundred years remained on Spencer’s list of ways he would rather not spend his time.

Comparable to going to church.

But Michael was in trouble. Spencer ground his teeth as his pounding footfalls up a stone outcropping rattled his bones. He had no idea what had knocked him down—a rabid dog, perhaps?—but two things were unmistakable: Michael was heroically attempting to lead the danger away from Spencer, and Michael had no chance of outrunning whatever this creature was.

Pausing at the top of the huge boulder, Spencer surveyed the undergrowth below. A wild rustle down to the right: Michael, hiding in a tangle of bushes at the center of a copse, his scent exaggerated by effort and fear. Why didn’t he stay still? On the other hand, what good would it have done? Spencer could clearly see, even in the shadows, a large shape slinking slowly, patiently, toward the thicket.

Spencer inched down the rock toward the animal, which looked for all the world like a wolf. The trees and the brush cast wind-tossed shadows, though, confusing his sight. More to the point, this was New York City. A more likely explanation made the animal a husky or some other crossbred dog, possibly rabid, and certainly feral or it wouldn’t be hunting in the park.

Spencer moved carefully and silently. His intent, once he’d put himself within the dog’s striking distance, was to call attention to his presence. He would be an easier target than Michael in the thicket, and the beast would leap. Spencer, whose strength certainly equaled that of a large dog and whose Noantri body could withstand whatever physical insult the dog might inflict, would defeat it. Unfortunately, that would likely mean killing it. It wouldn’t do merely to drive it away, back into the streets of the city, now that, rabid or not, it had reached the point of stalking human prey.

Explaining to Michael his victory over the thing might get tricky, but Spencer had had more than five hundred years’ practice in such matters. If he was lucky, Michael would remain hidden in the undergrowth and see nothing, in which case no explanation beyond a lucky bash with a large branch might be required. Spencer’s gaze scoured the ground for some such branch, and he found one and hefted it. Excellent: a weapon he could wield as he once had his saber. As he crept forward, his mind began to fill with the possible intimate consequences of this episode. Michael had acted courageously, leading the danger away from him, and he was about to play the hero himself, rescuing Michael. Adrenaline-fueled mutual gratitude and relief, in a warm bedroom on a cold night, offered a promising prospect. This ridiculous exertion might be worthwhile, after all.

Near the base of the rock he spied a flat shelf, perhaps three feet above the ground and ten feet from the dog. He leapt lightly down onto it, held his weapon at the ready, and called, “AHOY!” The animal snapped its head up, snarling. Spencer braced for its spring.

But before it could move, Michael burst from the thicket, shouting. Not at him, at the dog. Spencer didn’t know what he was saying, wasn’t sure it was in a language he spoke, and didn’t spend any time on the question: Michael was charging the dog, and Michael was naked.

Spencer found himself momentarily paralyzed, both by the sight—not entirely unfamiliar, but the relationship was new enough that he still found it breathtaking—and by the inability of his own mind to account for it. The animal similarly froze, torn between the two men, but Michael threw himself forward and tackled it and its decision was made.

So was Spencer’s. Michael might have suddenly lost his mind but that didn’t mean he had to lose his life. Spencer hurled himself off the rock and onto the swirling mass of fur and flesh. The rich scent of earth, Michael’s acrid sweat, and the aroma of blood—had the dog already made a kill?—assaulted him. He used the branch as a club, pounding its end on the dog’s head, but the dog just snarled and shifted its weight and the three of them rolled, tangled together, into the thicket. Brambles scratched Spencer’s face. The combined bulk of the other two thudded onto his chest and he realized three things.

One: the dog was huge. And coarse-furred, and gray. And muscular beyond expectation. This was no dog. This was a wolf.

Two: Michael was holding his own, clamping the wolf’s jaws shut with powerful hands, but he had no weapon. What had he expected to do, talk to the beast?

Three: Michael was, in fact, talking to the beast. Half speaking, half chanting, and accomplishing nothing that Spencer could see beyond tiring himself out while the wolf thrashed, kicked, and clawed at him with razor paws.

With Spencer still on the bottom of the pile, the wolf stopped moving. For the briefest second it seemed to stare into Michael’s eyes. Then it arched its back and dug its rear legs into the dirt. Snarling, it shook its head left, right, left, until with a roar it broke free. It stood, eyes glowing, jaws slavering. Then it lunged. Michael rolled desperately and lifted his arm in protection. The wolf rolled with him and Spencer was freed. The wolf’s pointed teeth, aiming for Michael’s throat, instead clamped onto his naked shoulder. Blood began to flow; Spencer could smell it. Without rising, he kicked hard into the wolf’s flank. The startled beast yelped, lost its grip on Michael and its footing. It stumbled, scrabbling to right itself.

Man and beast turned shocked eyes to Spencer.

He used the moment to jump to his feet and launch himself at the wolf. He aimed for the ears, vulnerable points on any animal. He’d yank the creature’s head up, get its jaws away from Michael. Then he’d break its skull. If he was lucky he’d find a rock to use; but he could do it with his hands. That was his plan. But the wolf was astoundingly fast. By the time he reached it—a second? two?—it had spun to face him. Its huge head angled and Spencer’s own momentum drove him into the gaping jaws. They caught his throat. The pain almost blinded him but, choking, he seized the snout and lower jaw, one hand on each, and pulled them apart. Knife-sharp teeth pierced his fingers. He managed to loosen the wolf’s grip, kicked at its belly, but his kick was weaker than before. He was dizzy; he was losing blood.

His hand on his own throat confirmed: the wolf had cut his jugular. In the long term—and for Spencer, what was not long-term?—nothing more than a nuisance, but here, now, with Michael in danger, Spencer felt the blood flowing between his fingers as a true loss, a failure, a tragedy. He tried to stand, but couldn’t. A strange sound began behind him. He expected the wolf to lunge at him again but its head lifted. It snarled, stood quivering. Spencer, lying on cold rock, turned his head painfully. The hallucinatory vision that met his eyes was Michael, naked, bleeding, bare feet planted on the soil, arms raised to the skies, howling at the moon.